Now that this book is printed, and about to be given to the world, the sense of its shortcomings, both in style and in contents, weighs very heavily upon me.”

Those are the first words of H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines, and I thought they were meant to be the author’s own sentiments about his novel. But the rest of the apology that follows from this sentence is signed by none other than Mr. Quatermain, the novel’s fictitious hero himself.

It is the first surprise among several in store for me about Allan Quatermain. So far, the sum of my understanding of this character comes from his appearance in both the graphic novel and the movie adaptation of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen,a Hallmark-produced TV-movie of King Solomon’s Mines, and a vague knowledge that there are several old adventure movies featuring Allan Quatermain exploring torch-lit tombs and swinging on vines, eventually giving rise to Steven Spielberg’s and George Lucas’ Indiana Jones series.

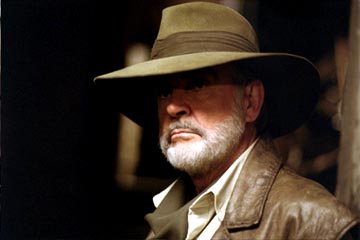

Sean Connery plays Allan Quatermain in the film of LoEG. He cuts a more muscular silhouette than the way Kevin O’Neill draws the same character in the original graphic novels, and one gets the impression that this Quatermain is a retired and possibly now-irrelevant shade of a once more dashing adventurer — in fact something more along the lines of Patrick Swayze in the aforementioned Hallmark television version: square-jawed, brawny, squinty eyes with that 100-yard stare. Essentially, I pictured Allan Quatermain in his prime (that is to say, as he would appear in his first adventure, King Solomon’s Mines) as Harrison Ford playing Indiana Jones in the 1980s.

But in actuality, Quatermain is a grizzled older man of smallish build and a distaste for taking foolish chances, even in his debut appearance. The novel is narrated in the first person by Quatermain, who tells us right away in Chatper 1 that he is “fifty-five last birthday” and “a timid man” who doesn’t like violence and is “pretty sick of adventure.” He leads elephant hunts for tourists in Africa and sends money back to England for his son Harry, who is studying to be a medical doctor. Quatermain is troubled by pain in his left leg, the result of an old lion-related injury. This placid, limping old family man is… our hero?

These days, the post-modern “anti-hero” is a well-known trope, and doesn’t really raise eyebrows. We’re used to “reluctant heroes,” or heroes who may have so much baseness in them we’re never quite sure if they’re meant to actually be the villain. These days, heroes like Casablanca‘s Richard Blaine, who sticks his neck out for no one; or the ne’er-do-well-turned-do-gooder Han Solo — are just so much background noise. But there was a day when heroes were properly “heroes,” near gods, sparkling and triumphant monuments of virtue, bravery and strength. King Solomon’s Mines was published near enough to that golden age of heroes that I expected Allan Quatermain to be Errol Flynn with a bullwhip and a necklace made out of crocodile teeth. I’m surprised to find in place of that image the slight, quiet, older man who is “sick of adventure.”

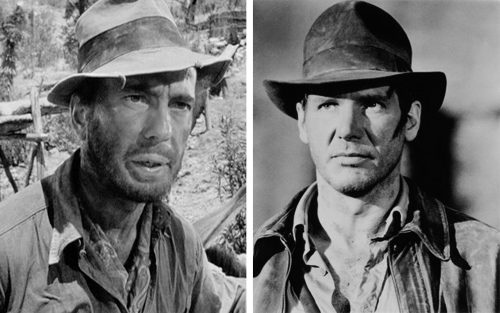

He makes Indiana Jones — who I had long believed to be a direct conceptual descendant of Quatermain — look like one of those spotless god-like heroes of yore. When in fact, Spielberg and Lucas invented their bullwhip-toting archeologist to embody the antithesis of that mode of heroism. They wanted something to give James Bond a run for his money, and they did it by dispensing with the luxury automobiles, the perfect hair, the white tuxedoes, the upper-class drinks and the ease with women which 007 had. The idea was to make Indiana Jones more of an “every man,” rougher around the edges. His iconic outfit places functionality over style. He sports a permanent five o’clock shadow. He drops things, miscalculates, and frequently finds himself in over his head. That desperate last-minute grab for his rumpled fedora is a very meaningful gesture. He’s a shop-worn hero, but not the first of his kind by a long shot. Humphrey Bogart had been treading those same mean streets long before Harrison Ford. As Rick Blaine in Casablanca, of course, he may have looked at times like Sean Connery as James Bond, but his selfish go-to-hell attitude was refreshing in its jadedness. But of course Rick had a heart of gold deep down, just as Sam Spade (The Maltese Falcon, 1941) and Philip Marlowe (The Big Sleep, 1946) had. In fact, his character Dobbs from Treasure of the Sierra Madre may be more responsible for Indiana Jones (at least in the costume department) than Allan Quatermain.

Bogart's "Dobbs" from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre; the influence on Indiana Jones seems like more than mere coincidence.

But I want to be careful that I don’t divorce Indiana and Allan completely. I think there is still some genetic makeup handed down from Haggard’s hero to Lucas’. Both have larger-than-life adventures with decidedly paranormal elements, yet both balance those nutty adventures with very human traits: Quatermain’s frailty and cowardice, Jones’ exuberant oversights and handicapping phobias (“Snakes! Why did it have to be snakes?”). Neither adventurer strikes one as highly composed, unflappable, smooth, or bloodthirsty. Jones may have a looser regard for human life than Quatermain does when push comes to shove (Spielberg looks back with regret at the famous scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark when Indy cooly dispatches a showy swordsman with a single shot from his revolver), but in each case blood is shed only as a provision for self-defense, and never on a first-strike basis.

The curious common denominator through all of this is Sean Connery. Connery was the first (and some, such as myself, might argue the best) man to portray Ian Flemming’s secret agent James Bond on film. It was in Connery’s hands that 007 became known for his cool-under-pressure style, the perfect hair even after bone-jarring action sequences. “Bond” became synonymous for fashionable clothing, top-of-the-line accessories, luxury automobiles and women that were every bit as fast and sleek, and responded every bit as willingly to his prompting. Sean Connery, then, is the mode of hero that Indiana Jones deliberately set out to deconstruct. Yet who should be cast in The Last Crusade as Indy’s father? None other than the original James Bond, but this time in a far more docile and dottering mode. As Henry Jones, Sr., Connery aided in dismantling the same archetype he helped to establish in the early 1960s. Indy’s dad can’t handle a machine gun, and participates in action sequences by stirring up a flock of geese with his umbrella, and then quoting poetry. His rumpled hat and tweed three-piece suit are a far cry from Bond’s tuxedo.

By casting Connery as Quatermain in the 2003 film adaptation of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, director Stephen Norrington is drawing upon Connery’s persona as the original James Bond. But dressing him in a wide-brimmed outback hat guarantees that audiences will also appreciate the Indiana Jones reference. And in so doing, Norrington makes Allan Quatermain quite literally the father of Indiana Jones.

In that sense, the casting seems appropriate. But that’s a post-modern, pop-culture sort of rationality which may suit the source graphic novel for League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (which itself practices a sort of post-modern witchcraft by uniting different heroes from Victorian fiction and treating them as though they might have co-existed in some kind of alternate history), but it does little in service of Haggard’s novel.

Back in 1950, MGM did very little to honor Haggard’s original vision, either. They forced a female lead into the story where there never was one (most versions of King Solomon’s Mines are guilty of this, but I confess it does seem like a good move), and cast Stewart Granger as Allan Quatermain. (The role of Quatermain was originally offered to Errol Flynn, who turned it down to star in the movie adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s Kim. King Solomon’s Mines was far more successful, and helped propel Stewart Granger to stardom. He reprised the role of Quatermain in a 1959 sequel called Watusi. Haggard actually wrote a sequel to King Solomon’s Mines called Allan Quatermain, but as far as I can tell Watusi is not based on that novel; in fact, Watusi claims to also be based on Haggard’s novel, King Solomon’s Mines.)

A loose comedy-adventure adaptation was made in 1985, starring Richard Chamberlain (who kind of looks like Chuck Norris to me) in the main role. The last live action version was the TV movie produced by Hallmark Entertainment in 2004, starring Patrick Swayze as Allan Quartermain (instead of Quatermain as it is in the novel). Finally, that ubiquitous action actor Sam Worthington is set to play him in some kind of sci-fi version of King Solomon’s Mines, in which Quatermain returns to planet Earth— well, enough said I guess. That sounds awful.

I think you’ll agree with me, even if you haven’t read the book and have only read my scant introduction to the character, that none of these actors seems to quite capture Allan Quatermain. At best, they manage to capture other characters (James Bond, Indiana Jones, etc.) as a sort of place-holder for the man himself. Sean Connery may have been the most age-appropriate, but he didn’t exude the retiring nature of Haggard’s elephant-hunting accidental hero. What I would like to know is, who would you like to see play Allan Quatermain?